Synagogues in Suriname

The synagogues, as seen in our gallery, were built with sand-covered floors. One idea is that clandestine converso synagogues in Portugal or in Dutch Brazil, where Portuguese conversos used to come to pray, had sand-covered floors so as to muffle the sound of the steps of those who came to pray. The Caribbean Jews explain the meaning of the sand by saying that as long as they are not back in Jerusalem, they are still trod ding in the desert. In fact the sand was also a useful protection against snakes and insects. Synagogues with sand-covered floors still exist; "Neve Shalom in Paramaribo. Zedek ve Shalom the Portuguese synagogue in Paramaribo and Beracha ve Shalom at the Jewish Savannah in Surinam were also covered with sand.

World War II.

During World War II there was a temporary revival of Jewish activities in Suriname. In November 1939, the first edition of the Jewish magazine Teroenga was published. On February 2, 1941, Suriname Federal Zionists organized regular meetings and applied to the Jewish National Fund.

On 24 December 1942, the Portuguese ship Nyassa arrived with about 150 Jewish refugees from the Netherlands and Belgium. Although provided with housing, some of the refugees were afraid to register their names. Shortly after the war, most refugees returned departed from Suriname; the last of them left in 1970.

Hitler’s order that all Jews in occupied Europe register with the State and what happened than to the Jews made a deep impression on the Jewish community in Suriname. At the time, many Surinamese Jews were in the Netherlands. In November 1942, different church councils formed a central committee for the defense of the Jews. The united churches were holding a special fasting, on 30 December 1942 and in the Bellevue theater a public protest was held by officials and representatives of other denominations.

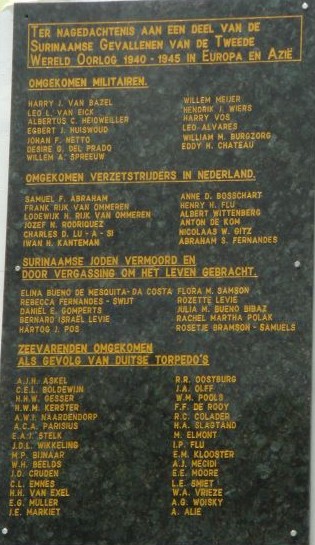

Listing of Surinam Jews, who died in World War II

In late 1933, the East-Indies (Indonesia) Division of the NSB (National Socialist Movement) was established, and by 1937 the division had 5,000 members. In 1937 they had about five thousand members. The NSB in Dutch East-Indies looks different as in the Netherlands. It was initially mainly an ultranationalist group of people who wants that the Dutch would keep Indonesia. Many Indo people ( Dutch-Indonesian descents) were members. The organization was anti-Japanese, and pro Dutch. In the late thirties it became clear that the NSB focused on racial purity. Then they lost many members. After the outbreak of World War II in the Netherlands, by order of the Dutch government, many members of the NSB in the Dutch East Indies were arrested and interned in Suriname. They are transferred in January 1942 to Suriname with the ship Tjisedane. Joden Savanne became an internment camp, no less than 139 people were interned. One of their tasks was to clean the village. They cleaned the graveyard and the village, what they found was a surprise. They make an inventarisation of the graveyard and had no idea that is was so large. More than 436 gravestones were uncovered. In July 1946, this group of NSB people went to the Netherlands.

Post World War II

The Saramacca Project

From 1946 until the mid-1950s, an American-Jewish organization called the Freeland League negotiated with Dutch and Surinamese authorities regarding the possible resettlement of 30,000 displaced Jews and refugees from Central and Eastern Europe in Suriname. Hopes were high when there was an initial positive reaction to the plan. But the project never came to fruition. So what went wrong? Read more ...

Inquisition

According to prevailing opinion, Jews have been present in the Iberian Peninsula since biblical times. With the formation of the Portuguese national entity under Alfonso I Henriques in 1143, there were already several Jewish communities in the territory that became Portugal. Their life had ups and downs depending on the reigning monarch and his attitude toward the Jews. In general, the Jews had their share of persecutions and pogroms interspersed with periods of peaceful life and prosperity.

With the growing numbers of repressions and trials by the Spanish Inquisition in the 15th century, Jewish and converso families began to cross into Portugal from Spain. The order expelling the Jews from Spain in 1492 forced them to find another place to live, and the nearest and easiest place to reach was Portugal. Between 80,000 and 100,000 Spanish Jews entered Portugal. The eight-month period of stay allowed by the Portuguese king was not extended, and the refugees from Spain were once again the objects of an expulsion order. Yet, shipping facilities to transport them elsewhere in the world were lacking, turning the Jews into illegals and leading to their being proclaimed king's slaves.

The death of Joao II in 1495 and the accession to the throne of Manuel the Fortunate (r. 1495-1521) gave the Jews a short term of respite and the enslaved Jews were released. But King Manuel's plan to marry the Infanta Isabel of Spain, daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella, the Catholic king and queen who ordered the expulsion of the Jews from Spain, put an end to this breathing space. The bride's hand was given to Manuel on the condition that Portugal be clear of Jews. On 4 or 5 December 1496, Manuel signed the order for the expulsion of the Jews before the end of October 1497. At the same time, however, the king impeded the Jews' preparations for leaving Portugal. The actual motivation behind the king's action was that for purely economic motives. The Inquisition in Portugal was characterized as crueler than that of Spain.

Whenever an opportunity for escape presented itself, the New Christians, Conversos, took advantage of it. They traveled far and wide in search of non-Catholic lands where they could cast off their adopted faith and resume their Jewish identity. Those who reached Western Europe headed for the Protestant centers of Amsterdam, Hamburg and, later on, London, where they returned to Judaism and established their own congregations. The New Christians were also attracted to Spanish and Portuguese colonies in the New World that offered both financial opportunities and a safe distance from the Inquisition. Madeira was an important steppingstone to Jewish settlement in America.

Brasil

The significance of Madeira to the history of Jewish settlement in America is that it was there that the Jews specialized in planting sugar cane and in sugar refining. The Portuguese governor of Brazil, Duarte Coelho Pereira, allowed several Jewish experts on sugar processing to settle in Brazil. Those Portuguese conversos now turned Brazil into the most important area for sugar production. Sugar expertise, considered at the time as almost exclusively Jewish, was linked to the history of the Jewish settlements in Martinique, Cayenne, Pomeroon, Suriname, and Barbados as well as to the positive attitude of the British and the Dutch to the Jewish set tlements in their colonies in the West Indies and the various decrees of rights and privileges to the Jews taking up residence in them. The Dutch West India Company organized a large-scale expedition in 1630 which resulted in the capture of Recife and Olinda in the Province of Pernambuco in Brazil. Dutch Jews are known to have served as guides and their knowledge of Portuguese let them act as interpreters. The Portuguese priest Calado relates that the Recife conversos rejoiced at the arrival of the Dutch expedition, since rumors circulated that the Inquisition was planning to have a permanent seat in Pernambuco." With the Dutch settlement of Recife, it can be fairly safely assumed that a portion of the sugar mills in Pernambuco were acquired and modernized by Jews." Seeing the industry develop, the Dutch governor, Johan Mauritz of Nassau, sent an expedition to west Africa to obtain and import African slaves for Dutch Brazil. As usual in the early history of the Americas, slave trade was exclusively in the hands of the occupying power, finding it a lucrative business.

We find that by 1645 the Portuguese, who had never relinquished their claim to Brazil, were putting more and more military pressure on the Dutch and fomenting uprisings against the Dutch by Portuguese inhabitants. Contacts between marranos in Spanish or Portuguese-held territories and Jews in British- or Dutch-held colonies resulted in large-scale trading, seen by the colony authorities as profitable and beneficial. Among the non-Jewish merchants, however, who did not enjoy the same contacts and facilities, this commerce created enmity and jealousy. In January 1654 the Dutch capitulated to the Portuguese forces. It was further determined that they had to leave within a three-month limit. It is assumed that about 150 Jewish families left Brazil for the Netherlands. When a group of 23 Jews fled, their ship was hijacked by pirates. They were put ashore in Jamaica. There they found a French ship who brought them to the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam. This group of 23 formed the core of what the largest Jewish community in history would be. "The others dispersed and settled for instance in Barbados, Curacao and New Amsterdam (New York), Suriname (after passing through Cayenne).

Suriname

Jews were among the earliest settlers in the plantation colony of Suriname. When Suriname was settled by the English in 1652, they already found some Spanish-Portuguese Jewish families living there peacefully among the Indians. (1630) They were living at Thorarica (Thorarica, nowadays the resort Overbridge) and came from different countries: Brazil, the Netherlands, Portugal, England. They settled the so-called "Jewish Savanne" with flourishing plantations bearing biblical names. This was the first permanent Jewish settlement, creating an interesting and unique historical phenomenon. The Jewish Savanne was considered a second Holy Land. The majority of names chosen for the Jewish settlements and plantations were those of places in the Holy Land - Beersheba, Dothan, Carmel, Mahanaim - and the town with its synagogue was called Jerusalem on the Riverside. Religious life was an integral part of daily existence. The planter did not work on the Sabbath nor did his laborers.

In 1665 the British Colonial Government granted several very important privileges to the Jewish community including freedom of religion, a Jewish civic guard, and the permission to work on Sunday while observing the Sabbath on Saturday. Probably nowhere else before the nineteenth century had Jews enjoyed so many political privileges, with so little intrusion on their lives. With the Dutch occupation in 1667, the Jewish rights and privileges were preserved, and special privileges were even added.

Remnants of the Joden Savanne, that had been the centre of Jewish life in the colony for several centuries, are still to be found up the Suriname River. Among them are the ruins of the oldest synagogue of bricks in the western hemisphere. In Paramaribo, the capital of the country, . Zedek ve Shalom and Neve Shalom are the Portuguese (and the German) synagogues, built and rebuilt on the very spots where the original buildings had been erected in the first half of the eighteenth century. The synagogues were built with sand-covered floors. Several theories have been proffered concerning this phenomenon. One idea is that clandestine converso synagogues in Portugal or in Dutch Brazil, where Portuguese conversos used to come to pray, had sand-covered floors so as to muffle the sound of the steps of those who came to pray. The Caribbean Jews explain the meaning of the sand by saying that as long as they are not back in Jerusalem, they are still wandering in the desert. In fact the sand was also a useful protection against snakes and insects. Synagogues with sand-covered floors still exist - "Neve Shalom in Paramaribo, Zedek ve Shalom the Portuguese synagogue in Paramaribo, and Beracha ve Shalom at the Joden Savanne in Surinam were also covered with sand.

The fate of the Jews was closely related to events in the colony; their material wealth as planters collapsed with the downfall of the plantation culture in Surinam. Following their emancipation in 1825, when they became full citizens, the Jews integrated further in Surinam society and, in the second half of the nineteenth century, gained increasing influence as merchants, doctors and lawyers, as well as civil servants and teachers. They also played an important role in the political activities in the colony, and constituted more than half the white population.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, it became customary for Jews who could afford it to send their sons to study in the Netherlands; most of them never re- turned to Surinam. Others sought their fortune elsewhere, believing Surinam held few prospects for their future. Some of the younger Jews assimilated into the general culture of Surinam society. As a result, the Jewish community shrank and lost its importance. However, for some time before these developments, Jewish religious and cultural life in the colony had already begun to lose its vitality; the absence of religious leaders and teachers contributed to a gradual spiritual starvation. The Jewish contribution to Surinam society did not completely fade; there are still many vestiges of the past.

Moreover, one cannot fail to detect traits in the Surinam culture which are undeniable of Jewish origin. The first settlers, the Portuguese, soon to be followed by German-Jewish settlers who, by the end of the eighteenth century, already constituted more than a third of the Jewish population.

The first historians of the Jews of Surinam - the Parnassim and representatives of the Portuguese community - correctly saw the history of the Jews as the integral part of Surinam's past. "Many Surinamese have African roots and are ancestors who have been enslaved. At the same time many Surinamese have Jewish roots, descended from slaveholders. They identify with slaves and consider themselves victims of slavery. Maybe it's difficult to identify with slaveholders. But that is exactly what is so interesting in the history of Suriname. The fusion of Jewish and African diaspora provide the backbone for the Surinamese multicultural society ".

To preserve its future in the face of dwindling numbers and proselytizing, Neve Shalom gradually has gone from Orthodox to liberal. Every 1st and 3th Friday at 19:00 pm and 2nd and 4th Saturday 8:30 am there are services. Entrance at the back of the building, in the Wagenwegstraat.